As I have mentioned more than once, I’m spending this year with Mark Nepo’s Book of Awakening, meaning that I begin my daily meditation by reading one of his 365 observations. More often than not, a series of readings—one day after another—will seem an awakening designed only for me. This past week, Nepo introduced me to the quiet teachers.

The quiet teachers are often ignored but are everywhere and are as solid as the ground upon which we walk. We know these quiet teachers by their “lessons [that] dissolve as accidents or coincidence…offering us direction that can only be heard in the roots of how we feel and think” (Nepo).

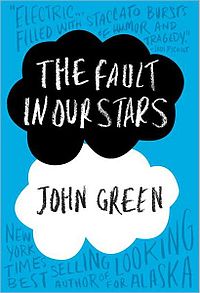

For me, the lessons have been clear but somewhat noisy for I am in the process of completely restructuring a novel I wrote seventeen years ago. What that means is the destruction of a weakly structured novel in order to salvage a stubborn story that has waited a long time to be told. It has required me to immerse myself into an old world, awakening characters long silent and provoking images fraught with memories. There has been much shattering of ideals but the shards of those ideals proved to be quiet teachers, the first of others that I met this week.

Nepo also introduced me to an observation from Megan Scribner: “‘I’m only lost if I’m going someplace in particular.'” I could not have described my own first attempt at writing a novel more succinctly. For over 80,000 words and seventeen years, I stayed with a story I no longer believed rather than facing the story that was trying to emerge. Once I began stripping away the façade, I heard the heart of the story and found myself at journey’s beginning: “Practice letting go of your plan and discover the path of interest that waits beneath your plan” (Nepo).

Not being attached to outcome or plan reveals the story waiting to be written. It is only when I have the courage to face failure do I heed the lessons of the quiet teachers. Accident and coincidence dissolve into the direction of the story. I am struck by the synchronicity of my own life’s direction with that of my writing life. Not for the last time, I am in awe at the oneness that is all.

“‘Be serene in the oneness of things and erroneous views will disappear by themselves'” (Seng-Ts’an) became clearer and clearer to me as I separated the heart of the story from the remnants of what was once a novel. All of the tearing apart and leaving of words is less difficult than I imagine. There are thorny moments but eventually, they give way to the relief of no longer having to hold up the façade of novel.

While the shininess of a new structure of a novel is a gift, the fear of idolizing structure at the cost of story, wherever it may wend, is a battle that will wage until structure and story support one another as a whole. I am confident in the lessons of the quiet teachers but mostly, I am vigilant for like life, writing is fraught with accident and coincidence as is the beating of my heart.

“As you enter your day, try not to reach for life. Try not to leave or arrive. Try to let life into you” (Nepo).